Kandy, a part of the central province hill country of Sri Lanka, is famous for its cool climate, soft mountain terrain and for many traditional and cultural festivals. Kandy of course is most noteworthy and world-famous for its landmark Buddhist heritage of the Dalada Maligawa (Sinhala for palace of the Tooth Relic of Buddha) or as is widely known the Temple of the Tooth Relic. The Temple, its origins dating back between the 14th and early 17th centuries AD, houses Buddha’s Tooth Relic brought to Sri Lanka in 313 AD from India. The Temple is said to have been built by King Vickramabahu II - initially as a royal palace. But it had been restored and rebuilt by various kings thereafter and was set apart exclusively to house the sacred Relic of Buddha.

But Buddhism itself came to Sri Lanka as early as 250 BC. Sri Lanka having been administered by the monarchy prior to its capture by colonial powers from the early 16th century, was then situated in Anuradhapura (North Central Sri Lanka) ruled by King Devanampiyatissa, who himself embraced and patronized the spread of Buddhism. Missionaries were sent over to propagate the philosophy in the island by the Indian Emperor Asoka, who himself had adopted Buddhism about that time. The missionaries included his own son Mahinda and daughter Sangamitta who spent over 40 years in Sri Lanka until their death, teaching and making disciples to preach the doctrines of Buddhism far and wide to both men and women. Interestingly, almost six centuries later, the Tooth was carried from India by Princess Hemamali hidden in her hair to ensure its protection and was enshrined in Sri Lanka. The Tooth found its way to Kandy, when the capital of the Sinhala kingdom moved to the Kandy district about the 14th or 15th century AD.

Kandy, known in Sinhala as ‘Mahanuwara’ (or large city) even today, is believed to have got its name after British occupation in Sri Lanka from 1796 onwards. The story goes that the British occupying officers in their travels to pay homage to the Kandyan king at the time pointed to the mountain terrain and making signs to them requested to know what the location in the distance was called. The locals are said to have looked at the mountains the Britishers were pointing to and described them as ‘kande’, referring to the Sinhala literal word for mountain. Since then the British referred to it as Kandy, the closest pronunciation they came to the word used by the locals. As humorous as this may be, the name Kandy that came to stick was not far from the informal name given it by the then administration – ‘kandu-rata’, literally meaning hill country.

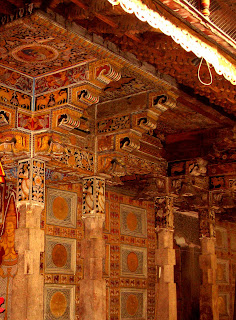

The Temple of the Tooth Relic houses not only the sacred tooth of the Buddha, throughout the year luring Buddhist pilgrims from both within and without Sri Lanka and tourists, but is also famous for its ancient artifacts and vibrant murals, now centuries old. The murals, hand painted by specially selected artists and artisans working for the royal court, have used natural dyes and motifs that speak volumes and have captured the culture and customs of its time. Each painting weaving the story of Kandy and a lesson in history where one can relive the life and times of the ancients. The stone and ivory inlay work of the Temple too through its carefully crafted designs graphically relays important architectural information of the period and events of the time. Because the city is steeped in culture and tradition, it earned the prestige of being entitled a ‘Cultural Heritage site’ by UNESCO in 1988.

The Temple in itself has been cause for national pride for centuries and informally stands as the cultural heritage of not only the Buddhists but also the Sinhala people as an ethnic group. About 74 percent of the Sri Lankan population comprises ethnic Sinhalese, while the rest is made up of Tamils, Muslims, Moors or Malays and Burghers or Eurasians – the latter the descendents of mixed marriages between the colonial occupants and the local Sinhala population. Of the 74 percent Sinhalese, close to 70 percent are Buddhists (of the Theravada chapter of Buddhism). Therefore, in Sri Lanka, the ethnicity Sinhala and the philosophy Buddhism are very closely linked and many cannot make the two apart. This has resulted in the popular yet incorrect notion that ‘Sri Lanka is a Sinhala-Buddhist nation.’

The Temple in itself has been cause for national pride for centuries and informally stands as the cultural heritage of not only the Buddhists but also the Sinhala people as an ethnic group. About 74 percent of the Sri Lankan population comprises ethnic Sinhalese, while the rest is made up of Tamils, Muslims, Moors or Malays and Burghers or Eurasians – the latter the descendents of mixed marriages between the colonial occupants and the local Sinhala population. Of the 74 percent Sinhalese, close to 70 percent are Buddhists (of the Theravada chapter of Buddhism). Therefore, in Sri Lanka, the ethnicity Sinhala and the philosophy Buddhism are very closely linked and many cannot make the two apart. This has resulted in the popular yet incorrect notion that ‘Sri Lanka is a Sinhala-Buddhist nation.’ However that may be, this popular notion led to the Temple being targeted by the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam – a former separatist outfit in North and East Sri Lanka) in 1998. Kandy, that had been secured in the past against foreign invaders (with the support of guerilla forces known as the Laskirinne, sponsored by the royal house) such as the British forces no less until their forceful takeover in 1815 and the banishment of the then presiding King Shiriwickremarajasinghe to South India, had come under attack in the post-colonial era and modern times in the early 20th century by its own countrymen, further creating an emotional rift between the Tamils and the Sinhalese. This was perhaps the intention of the terrorist faction, in the first place: to wound the sentiment and emotional attachment of the Sinhalese to the Temple and not merely the physical damage to it. The well-preserved roof of one of the domes of the Temple was severely damaged as a result as far as the physical outcome of the bomb blast was concerned. This was later rehabilitated using pure gold – so sacred and of such national importance was this Temple to its devotees. I suspect this grand display of opulence was a symbolic reply to the intentions of the LTTE – ‘down but not out.’

Growing up, Kandy situated only about 100 kms from Colombo was always a choice holiday destination for us children during the summer vacation. While the inter-monsoonal periods in Colombo saw soaring temperatures of 28 – 32 C, Kandy remained a cool 20 – 25 C back then. It was also a popular midway point for those who liked to travel further to a more chilly and scenic destination – Nuwaraeliya, also known as Little England.

I had family living in Kandy and so much of the month-long school holiday in April each year was spent with cousins there. It was a welcome change from the humidity and bustle of the capital city Colombo, but I appreciate Kandy more now as an adult who can comprehend differences and appreciate them that much more. The April vacation is Sri Lanka’s longest holiday season and the most celebrated one, as it is during this month that the nation celebrates its traditional New Year – by both the Tamils and the Sinhalese. The New Year is celebrated at this time of year, following the lunar calendar when the sun completes its revolution covering the astrological twelve parts of the sky or solar system.

The New Year season has always been a special time for my family because half of it has a Buddhist heritage and past, and so all the cultural festivities were celebrated in all its traditional splendour. All of my cousins, my sisters and I would congregate during the holidays in Kandy and engage in preparing traditional sweetmeats, participate in the traditional games that in themselves have helped preserve our culture and no holiday has ever seen an end without at least one visit to the grand Temple of the Tooth. I have accompanied my Buddhist cousins to the Temple not to observe religious practices but to people-watch and to gaze at the murals and the beauty it encompasses. To this day, whenever I am in Kandy, I visit the Temple if only to drink in the quiet serenity of the place and to observe the simple devotion of people united in their journey to attain a higher sense of being. In a word, the Temple personifies serenity. The Temple is also popular for Buddhist pilgrims during the following month when Buddhists observe Vesak – the observance of Buddha’s birth, death and enlightenment.

However, Kandy’s significance lies not only in it being the residence of Buddha’s Tooth Relic nor for its climate alone. Kandy makes one point of Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle. The other two points of must-see value are situated in Dambulla and Anuradhapura towards the north central vicinity of the island.

My father and his brothers schooled at the Kingswood College in Kandy, one of the many famous missionary schools in the hill country. Founded under the Methodist mission by the British, my father has regaled us as children with numerous tales of his adventures at boarding school, pranks played on and quirks and peculiarities of his English schoolmasters. On Sundays the boys were dressed in their Sunday best and compulsorily taken to church. It is in this light that years later, attending St. Paul’s in Kandy at Easter brings on nostalgia for all of us.

As Kandy is situated in a hilly region, most houses are built along mountains. The drive up and around mountains to visit friends and family was mostly a fun adventure, excepting for the odd bout of nausea my disposition was prone to (before my discovery of the wonder-drug Avamin). Apart from Kandy town, much of the district is agricultural and mostly cultivating paddy. In the hilly region, however, paddy is cultivated using the ‘step’ cultivation method, vertically layered, skirting around the mountains separated by agriculture channels between them to provide water. The different hues of lime green of the paddy, contrasting with the white dotted houses against the most often clear blue sky is breathtaking. The views are most enjoyed by locals and tourists alike coming into Kandy by train. The special observation car of the Colombo-Kandy train rarely fails to elicit from within it oohs and ahs in appreciation and wonder of the scenery along the way. As children, taking the train to Kandy, we had hours of fun counting the number of tunnels the train passed under. We would all gather around to get a glimpse of a mountain crag affectionately called ‘Bible Rock’ after its obvious shape from a distance. These mountains would transform before our young eyes into the shapes of giant animals and humans and we loved creating stories about how they came to be frozen in time.

Kandy is known for its artisans and the variety of arts and crafts such as wood carvings, painted demon masks, copper and bronze ornaments and semi-precious jewel-studded elephants and silver jewellery. The clothing of ordinary people is also very different and unique to Kandy. The osari or ‘Kandyan saree’ typically worn by the ‘up country’ Kandyans is now synonymous with Sinhala traditional dress for women. Its difference from the usual ‘Indian saree’ is in the way it is draped and the various styles adopted in wearing the blouse or the upper garment. Traditionally, it was worn with long sleeves made of fine traditional cotton lace, also locally produced in Kandy. Another unique feature hailing from Kandyan Buddhist houses, now also seen in old-fashioned Sinhala homes elsewhere in the country is the ‘sesath’. These were historically the hand-held fans that flanked the King on either side at his royal court and in public, portraying royalty and power. Today these are seen positioned in the living rooms of Sinhala traditional homes to portray age-old custom, tradition and heritage.

The Mahaweli – Sri Lanka’s longest river beginning in central Sri Lanka and falling to the sea at Trincomalee – a town on the north-east coast of the island - runs through the Kandy town like a lifeline connecting all its inhabitants. The Mahaweli that surrounds the Temple of the Tooth gives way to a large lake in the middle of the town, so dreamy at evening with light cast from street lamps and from the glimmer of the moon upon it. It is so romantic and serene that you just cannot miss the young lovers holding hands and dreaming of their futures on the benches upon the banks of the lake.

The Mahaweli – Sri Lanka’s longest river beginning in central Sri Lanka and falling to the sea at Trincomalee – a town on the north-east coast of the island - runs through the Kandy town like a lifeline connecting all its inhabitants. The Mahaweli that surrounds the Temple of the Tooth gives way to a large lake in the middle of the town, so dreamy at evening with light cast from street lamps and from the glimmer of the moon upon it. It is so romantic and serene that you just cannot miss the young lovers holding hands and dreaming of their futures on the benches upon the banks of the lake. But even the serene and majestic Mahaweli was not spared the horrors of the political upheaval in the island’s past. I remember once hearing from my cousins that a few months before one of our vacations to Kandy how they had witnessed human bodies floating along the Mahaweli – those killed during the 1989 insurrection, yet another bleak period in an already dark past in the country’s modern political history. Standing in my cousins’ garden, high up on a mountain, breathing in the fresh woody air and looking down into the gently flowing river below with cranes hovering on either bank and kingfishers traipsing along the water for their afternoon catch, it seems almost unbelievable; and yet the river hides in its perennial memory dark secrets of human history.

Shutting away, at least momentarily, the darkness that has plagued the whole country and all its people over the last several decades, my thoughts move on to the Kandy market, with its pavement shops full of various knick-knacks, traditional sweets such as the kondakavum, dosi, dodol and aasmi, and the numerous fruit vendors. The genuine leather products manufactured in Kandy are a real treat to visitors. Of course no visit to Kandy is complete without indulging in hi-tea at the Queens Hotel across from the Temple of the Tooth. This olden hotel constructed during British occupation still attracts for its old English architecture as well as the age-old charm of the interiors and its service. The tea at such hotels is served to the right boiling consistency of finely selected quality teas with immaculate tea service and paraphernalia and is just the perfect beverage to enjoy on a rainy late afternoon in Kandy with either a good novel or good company. Of course in Sri Lanka, one hardly needs a perfect time to enjoy a good cup of tea. The delectable cakes, pastries, mini decked sandwiches and biscuits served as accompaniments to tea, leaves one spoiled for choice. Still on food, one of my favourite institutions in the city that I must visit even for a quick stop driving through Kandy is the Devon Restaurant and Bakery. It is easily over 100 years old and yet the aromas, the tastes and the quality of food served here - best for its traditional Sri Lankan fare like hoppers (appa), string hoppers (indi appa) and rice and curry – are consistent and inviting.

The best season to visit Kandy is in August when the event Kandy is most famous for takes place – the Kandy Esala perahera or procession. Hosted by the Temple of the Tooth, this event spans over two weeks, taking on festival-like proportions and equally charged preparations. Thousands of visitors throng Kandy town, calling for special traffic and security arrangements. At this time of the year, hotel occupancy in Kandy is completely saturated and to accommodate guests and visitors to Kandy even private homeowners are known to open their homes to strangers. I have at least two vivid memories of witnessing the perahera – once as a child of about eight high up on my father’s shoulders amidst the thronging crowds, and more recently a few years ago during a workshop in Kandy, playing guide to several foreign colleagues. The perahera is a rich concoction of the best of Buddhist and Sinhala culture. The procession displays various traditional dancers, martial artists, flag bearers and musicians depicting the various pre-colonial districts coming under the jurisdiction of the monarchies both of the ‘up country’ or hills as well as the ‘low country’ or plains of the island. The procession takes on a carnival atmosphere with its stilt-walkers, traditional drummers, whip dancers and fire stunts. These occupations requiring immense skill and perfection are handed down from generation to generation, in service of the Temple. The highlight of the event and what most visitors, specially children, come to see is the procession of decorated elephants. At the last procession there was a display of over 120 elephants, dressed in fine clothing and vibrantly lit up.

The last attraction and the ultimate reason for the procession is to parade Buddha’s Tooth Relic mounted high up on a specially trained elephant, adopted, bred and dedicated to this purpose by the Temple mahouts. Some of the elephants showcased in the procession are owned by the Temple Trust and are cared for with special treatment for the purpose of the perahera. They are sometimes brought out to the Temple gardens for people to touch, as they are considered sacred to devotees. At the end of the three to four hour-long procession, the special guests, the chief reverend monk presiding at the Temple and the Diyawadana Nilame – a revolving sacred and powerful appointment made by the Temple Trust and highly honoured even by the President of the country – parade in their traditional finery. It is the Diyawadana Nilame that would finally undertake the task of taking down the sacred Tooth Relic and offering it for a blessing to the monks of the Temple and then depositing it back in its sanctuary within the Temple. The procession is held to provide a chance to Buddhist devotees who make the annual pilgrimage to glimpse the Tooth and pay homage to it, thereby invoking great blessing upon their lives.

Just out of Kandy, the well-maintained Botanical Gardens and the Peradeniya University, the former a national treasure of plant life and the latter one of Sri Lanka’s prestigious academic institutions, hover as major landmarks of the district. On the way back to Colombo along the Kandy Road is situated the world-famous Elephant Orphanage at Pinnawala. I recall a school class trip to Kandy years ago where my friends and I picnicked at the Botanical Garden, smuggling a boom box hidden in our shoulder bag to dance to. I remember belting out tunes with my Convent School girlfriends at the top of our by-then sore voices and swinging from some of the more-than 100 year old trees in girlish glee, while our good-humoured teachers tried hard to dissociate themselves from us after giving up on trying to tame our rowdy ways. At the end of the day we each took turns making speeches thanking almost everyone we could think of, including passing couples in love (much to their chagrin and embarrassment, which they quite plainly let us know), little children, the mayor of Kandy and the President of Sri Lanka for the lovely time we had had. My visit more recently to the Peradeniya campus was more somber and quieter – to train and deploy a group of new graduates in some field research projects.

But my visit to Pinnawala on several occasions, always accompanied by small children have been nothing short of blissful. The orphanage officials encourage visitors to get involved in caring for the maimed or disabled elephants. The public gets a chance to feed these majestic and yet gentle animals and watch them bathed daily by the animal caretakers. Sri Lanka’s elephant population has been steadily growing as years ago administrators and environmentalists took pre-emptive measures to protect their habitat by reserving sanctuaries and carving out a channel for the free movement of elephants from the southeast of the island right along to the northwest interiors. Back then, the Elephant Pass isthmus bordering Kilinochchi and Jaffna peninsula in the north of the country was so named for this very purpose. However, in the very recent past, Sri Lankan farmers, environmentalists and Park officials have been locked in a three-way debate on the increasing incidence of elephant poaching on the one hand and the death of farmers and the destruction of their crops and homes by elephants, specially during harvest times. Electric fencing resorted to by authorities in the past has not brought about an effective solution to the problem that has brought untold misery to villagers in elephant-prevalent parts of the country who are torn between their love for these animals in their Buddhist practice of ahimsa (non violence and abstinence from cruelty to animals and all living things), and their desire to stay alive and protect their livelihoods and their homes.

Kandy, to me, holds pleasant memories and experiences. These memories and feelings are reinforced by the fact that my times spent up in the hills of Kandy were those in which I felt far away from the ugly realities that unfolded daily in other parts of Sri Lanka. Almost as though in Kandy one could find a different country, not bothered by the threat of war nor shackled by the teeming rat race of Colombo. Simply breathing in the clean air, watching the days go by in serenity and quietude with beauty and a wonderful sense of peace enveloping you on every side.